13 min to read

Behind the scenes : watching media on the browser (I)

Go through the whole journey of how media are being play on the internet.

Have you ever thought about what it’s actually happening when you click on the play button on your favorite media websites, maybe Netflix, Youtube, Twitch or what ever websites serving media streaming. How are those media data being transferred over the internet? How do they package them? And how do browsers handle those data and represent them to users? Let’s take a deeper look at that to see what’s going on.

Downloading Media Data

The content providers, such as Youtube, would put media content on their servers and then distribute them onto worldwide CDN, which referes to a geographically distributed group of servers which work together to provide fast delivery of internet content because users won’t need to go back to the actual data server which might be far from users in geographically.

When browsing a website containing a media element used to play media, it would start requesting data from the server. The process of downloading media data from servers is called “Progressive Download”. Between servers and your devices, a media file would be splitted to many small chunks and be packaged into HTTP response packets, being transferred over the internet bit by bit.

How many data do browsers need before media starts?

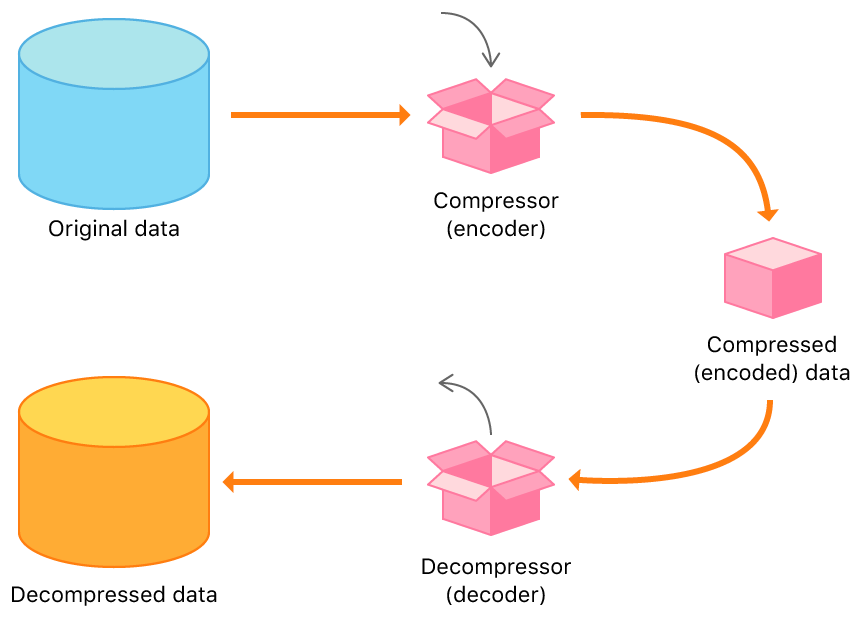

First thing you need to know is that the media data transferred over the internet are all compressed data, which is also called encoded data. That helps to reduce the file size by ten to twenty times. In audio compression, each audio file are independent, so decompressing one single audio frame is possible. However, in video compression, they’re usually not all independent. Imagine that if two video frames have almost 90% similarity in their scene, in this situation, instead of saving two frames in the original size, we could save only one original frame, and record the difference between two frames for another video frame, which help reducing the amount of data we need to store.

That is a basic concept of video compression, and the real compression algorithm is definitely way more complicated than that. Therefore, for video data, we need to get enough amount encoded data before we can output one uncompressed frame, which is also called decoded data. Thus, the answer is that having partial data is enough, but the amount of data that browsers need varies on different media files.

In the HTML specification for media element, it defines different levels of state indicating if media is ready for playing or not, which helps websites to know when they can starts playing media. After media starts playing, browsers would keep downloading remaining media data and store them beforehand, which we call caching data.

The reasons of caching data are (1) to keep playback smooth all the time. If we don’t have enough data to decode, then we have to wait for more data again, which would be not pleasant for users. (2) to improve the speed of jumping to other position in the file, which is called seeking. Once we have a whole file, we can jump to the arbitrary position in that file without requesting data from the server again. Requesting data from servers is an expensive operation, which would be done by using HTTP range request and we want to avoid that as possible as we can.

How many data would browsers cache?

It depends on each browser’s implementation, in Firefox, we cache at most 500 MB per process. That raises another question, can websites determine how many data would browser download ahead? Because they might want to buffer less data to save the bandwidth. And yes, that can be done by using Media Source Extension API that gives websites more ability to control the data they want to play, such as controlling the amount of buffered data and adaptive bitrate streaming.

Wait? “adaptive bitrate streaming”? It sounds like a cool stuff, what is it and why it does matter in terms of streaming media on internet?

Adaptive Bitrate Streaming (ABS)

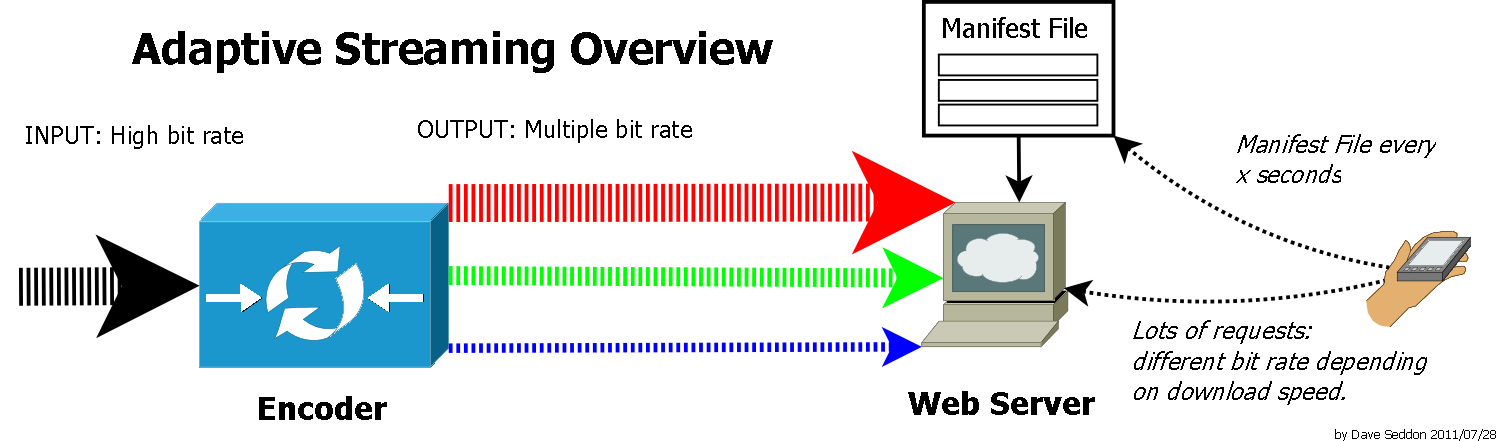

Imagine that you’re in a moving train where the internet accessing is not constantly stable, sometime you get LTE, but sometime only 3G. If you want to watch a video under this circumstances, you might probably not be able to watch same solution video smoothly all the time because the internet speed varies, which would lead to a frequent buffering. That is why we need the adaptive bitrate streaming that would determine what quality of video is the best choise for user’s watching experience by considering user’s internet bandwidth and the CPU usage.

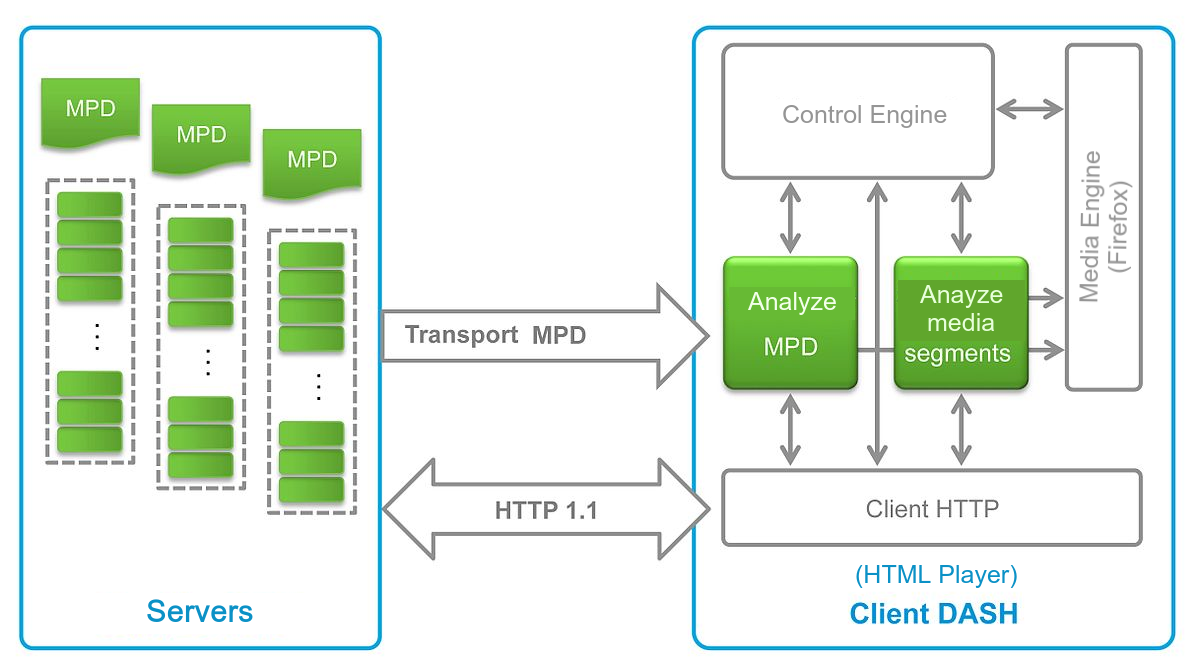

The basic idea is that the content providers would prepare videos with different resolutions on the servers, and give a list that defines the corresponding relationship betweens the bandwidth and video files, the timestamp for vides, media-content availability and other encoding details. Each resolution video would be further splitted into way smaller videos and be listed under the category of that resolution. Then the media player, which users are using, would reference that list and determine what video user can watch smoothly according to their internet bandwidth and computer ability by using Media Capabilities API.

There are serverl different implementations for ABS, but the most popular and well known two in these days are MPEG-DASH (Dynamic Adaptive Streaming over HTTP), which is developed by the Moving Pictures Expert Group (MPEG), an international authority on digital audio and video standards, and HLS (HTTP Live Streaming) developed by Apple Inc. MPEG-DASH uses mpd file format as its media description list, and m3u8 is the format HLS uses.

In term of the compatibility of these implementations, HLS has wider support than MPEG-DASH and the main reason is that iOS devices natively support HLS which makes websites won’t be able to ignore the huge amount of users on iOS. The native support means that website can assign .m3u8 and .mpd file resource directly onto the src attribute of the media elements, rather than assigning media file, such as .mp4, .webm. Therefore, the job of supporting those implementations is mostly done by using javascript and Media Source Extension API, which is usually implemented by various html players (eg. dash.js, hls.js) that actually control what media resolution users would watch. By using those players, users are finally able to enjoy the benefits which ABS brings.

Media Content Extraction

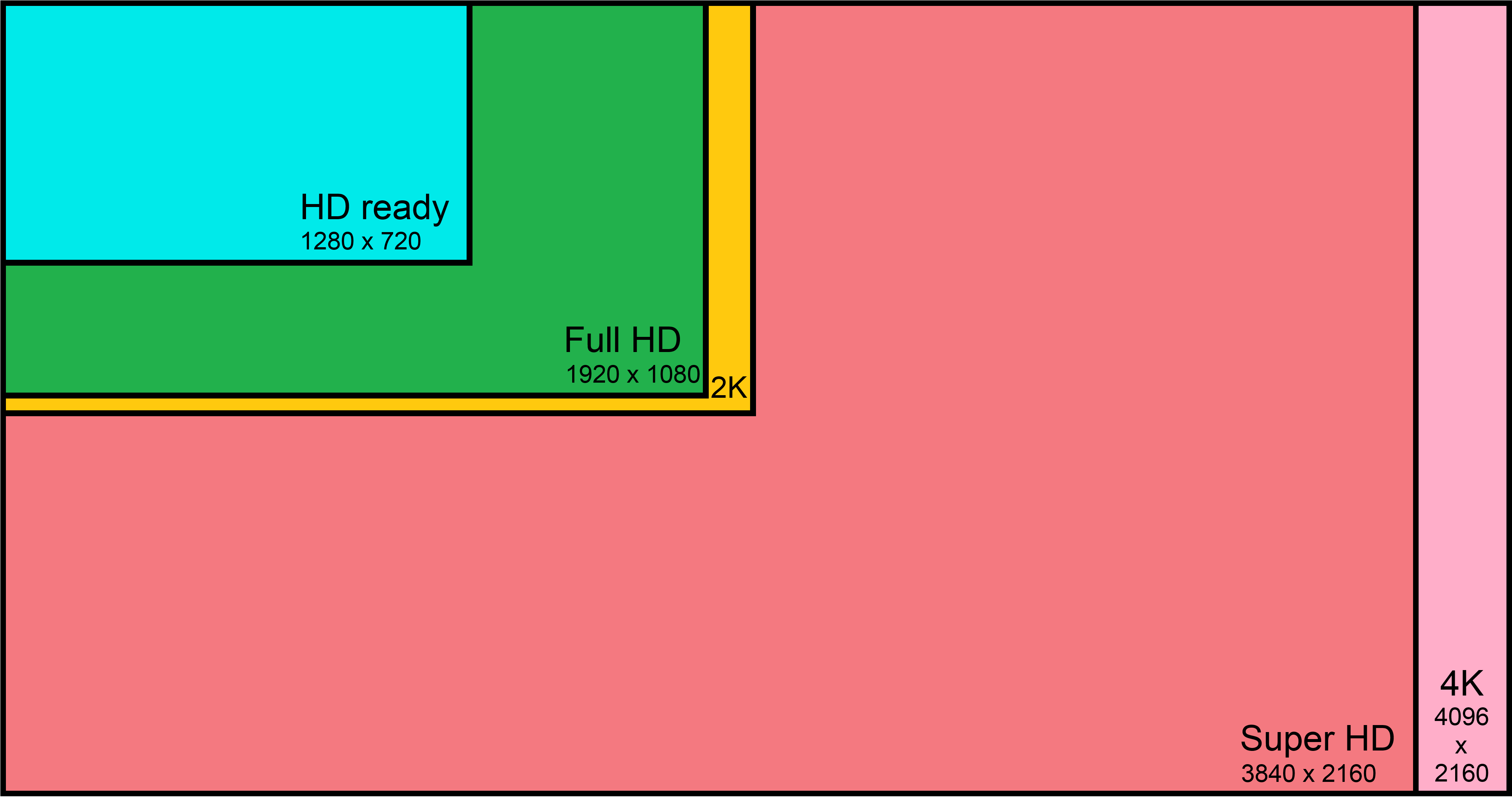

Before discussing extracting media, let’s dive deeper into compressing and packaging media, because the raw media file is really huge. Take a Super HD HDR video as an example, one single frame takes around 31.1 MB, If it’s a 24fps video, then only 1 second long video clip needs 746.4 MB data, which is a huge requirement for users.

3,840 (pixels) x 2,160 (pixels) x 3 (colors) X 10 (color depth)

= 248 (Mb/frame) / 8 (bits/byte)

= 31.1 (MB/frame)

Therefore, we need to compress those data into a smaller size without losing too much visual details, we call this process as encoding. There are various encoders you can use, all of them have different features and compression ratio. Eg. using H264 (a video compression standard) to encode the same data, one second media would only need to take 22.9MB, which is a huge data save.

Next step is to package those data into a container. It’s like what we do in a real life, whenever you want to send something to someone, you need to package them into a box, a mail envelope, a bag or whatever it’s. Similar thing here, to put those encoded data into a media container. Here is the list of different media containers, each container has its own rule for what kinds of encoded media can be put inside. We won’t reveal too much detail here, because that would be a long story. The process of packaging encoded media into a file calls muxing, and softwares do that is called muxer.

Therfore, the media content extraction follows the exact opposite steps, first to extract the media data from the media container, which is demuxing, and decompress data to audio/video frames, which is decoding. The process of demuxing and decoding is the key of determining if users can watch media or not, which is probably the most important part in browsers’ media pipeline.

However, if the media content is protected by Digital Rights Management (DRM), then performing decryption before demuxing data is needed. That would need the help from the Content Decryption Module (CDM) softwares, which are responsible for communicating with the licence servers and know how to decrypt the encrypted media content. That is what users would encounter when watching video on Netflix.

In addition, different browsers uses different CDM, Firefox and Chrome uses Widevine supported by Google, Microsoft Edge uses PlayReady and Safari uses FairPlay.

Play Audio Content

Now we’ve had some decoded data, what spell would browsers cast on them to make them playable?

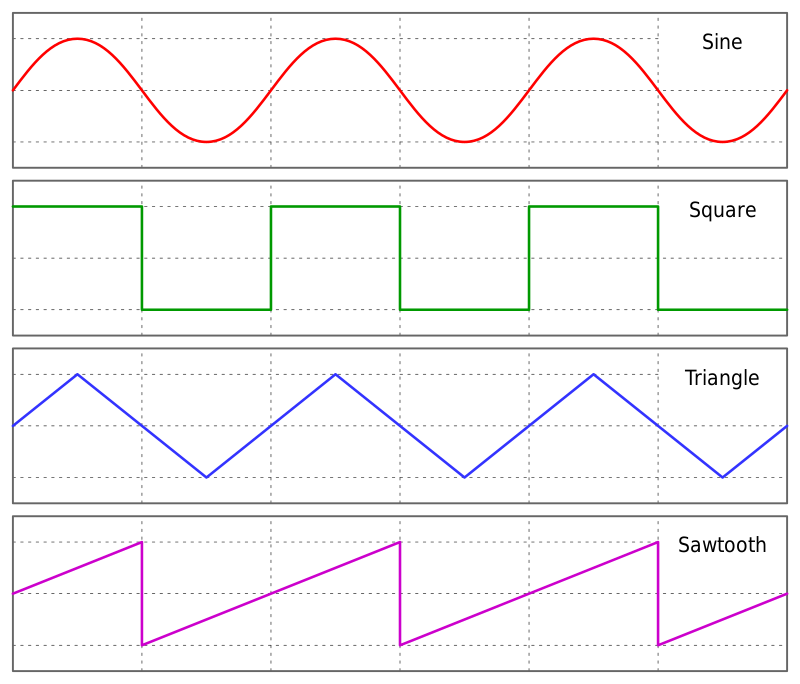

Let’s talk about audio first. In order to know the magic, we have to understand how does an audio file get formed from the analog to the digital. In the physical world, audio consists of different kinds of audio waves, which might vary in their shapes (sin, square, triangle and sawtooth), amplitude (the loudness) and frequency (how fast does the wave repeat).

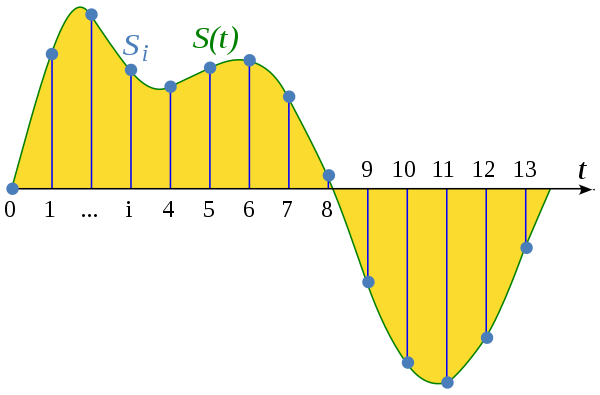

In order to transform a continuous wave to a series of discontinuous singal data and make them as close as possible, what we can perform is, in a certain period of time, to pick as many as possible points from the audio wave and record their value. Once connecting those points together, it would look similar like a wave, but just not as smooth as the original one. This step is called Sampling.

The higher amount of points being sampled in an unified interval, the closer the wave would be as the original one. (File would get bigger as well!) The most common sample rate is 44.1 kHz, which is 441,00 audio samples per second.

In addition, the sound we hear in daily life are not always coming from one directions, they can come from anywhere, and the human being are able to identify where the direction does a sound actually come from. So people started to think how can make digital audio sound more realistic. Then stereophonic sound got created.

That is a method used to creates an illusion of multi-directional audible perspective. For instance, using two audio sources which are made silghtly different by shifting time or adjusting volume, then one for the left ear, and another for the right ear. That can make audiences feel that the sound source is more realistic, not plain and static.

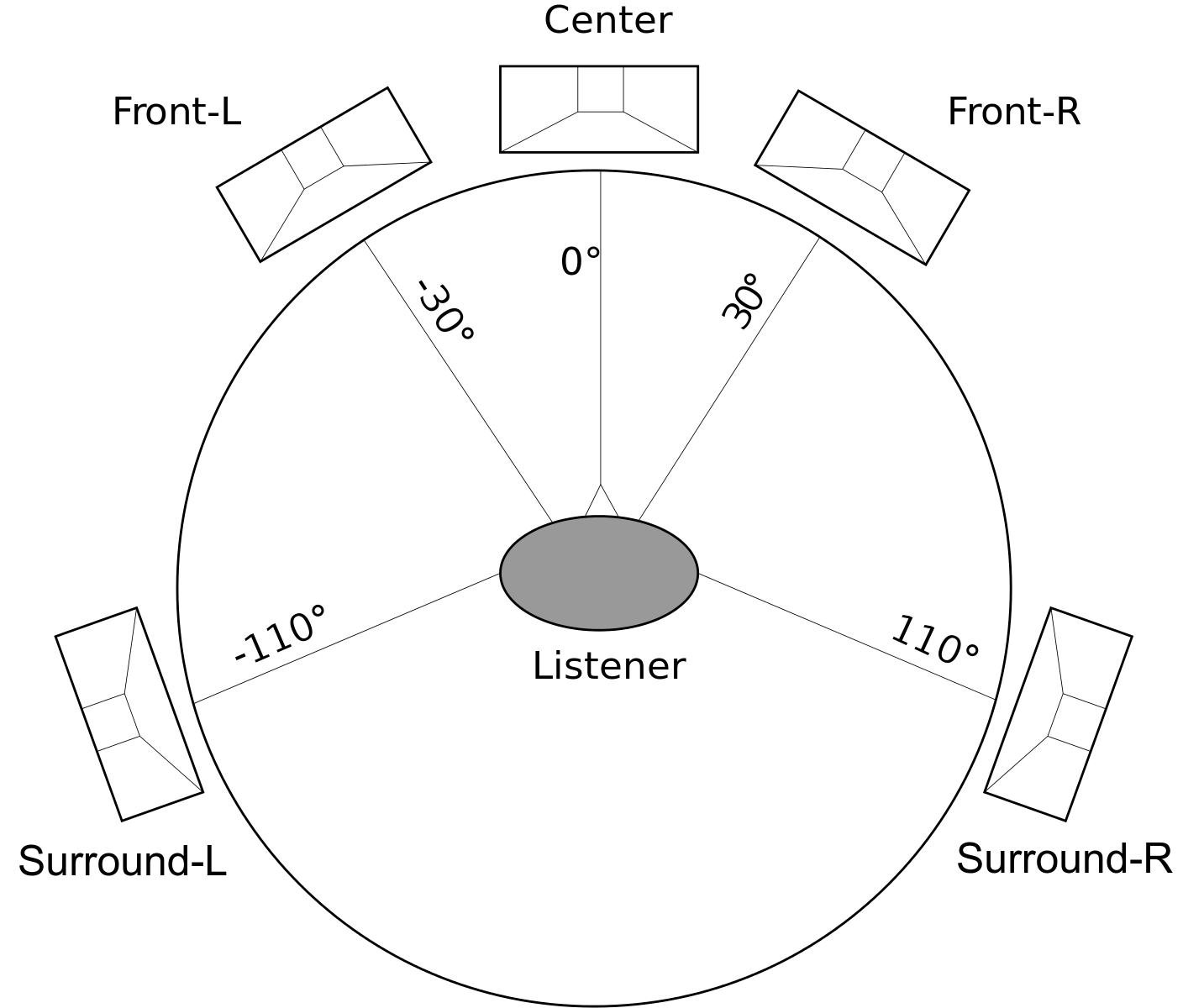

Therefore, we can create more spaces for storing different audio sources. We call that audio channel, and audio which has multiple channels are Multichannel audio. The Mono refers to having a single channel, and the Stero is having two channels (left and right). Some complex audio channel setup can even be up to five channels or more, eg. 5.1 or 7.1 which are categorized to surround sound.

OKay, let’s have a short break here and conclude what we’ve had so far. An audio files consists of many many audio samples, and the samples amount is determined by the sample rate and the audio channel amount, and the sample duration is determined by the sample rate. Assume that we have a 1 minute long stero audio file, which is sampled in 44.1kHz. How many audio samples we would get for this file?

60 (seconds) * 44,100 (samples/seconds) * 2 (stero: left/right)

= 5,292,000 (samples)

Then next coming question is, if a user also has stero audio speakers. How do browsers know which data belongs to the left or the right speaker? Furthermore, if the input and output source both have more a complex setup (eg. 5.1), how are those audio samples being arranged in an audio file?

People as smart as you would probably start thinking about there must be a standard used to define the order for different audio channel layouts. Yeah! There are several different standards in use, and the SMPTE/ITU order is the one of the most common the one and Firefox also uses that in all our audio samples.

Take 5.1 (3F2-LFE : means 3 front speakers, 2 rear speakers and 1 for low-frequency effects) as an example. The data for the left channel should be put in the first place, following with the data for the right channel, and so on.

Channel order : L-R-C-LFE-LS-RS

Abbreviations : Left(L), Right(R), Center(C), Low-frequency effects(LFE), Left Surround(LS), Right Surround(RS)

Another question pops out, what would happen if the input and the output have different audio channel layout?

If we only have stereo data, how can they be played on 5.1 sound system? What data should be filled into those channels that don’t exist in stereo? Eeg. center. Apparently we need some conversion.

When the input has more channels than the output, we need to perform downmixing. When the input has less channels then the output, upmixing is required. That would simply be done by applying the original data with a conversion matrix, which is defined in this specification. If you’re interest in more details on how is downmixing/upmixing performed, check this article.

Then browsers finally are able to send those audio data into the audio hardwares by using some audio back libraries. In Firefox, we use cubeb to perform cross-platform(Windows/MacOS/Linux/Android) implementation. By wrapping platform specific details in API cubeb provides, Firefox are able to easily send data to audio driver and play them to users.

Is the story over? Not yet! We’ve not talked to video, and how does video cooperate with audio during playback is still a mystery to us. In the next part, I’m going to discuss those myterious parts, stay tune!

Comments